Getting High

Huxley on Mystical Experiences and the Question of Psychedelics

“I was able to experience what the mystics were for some reason able to experience spontaneously,” a participant in an experimental study investigating the effects of psilocybin reported, the implicit assumption being that most people are incapable of having mystical experiences without the aid of external interventions: “I don’t think that . . . my experience was less than theirs.”

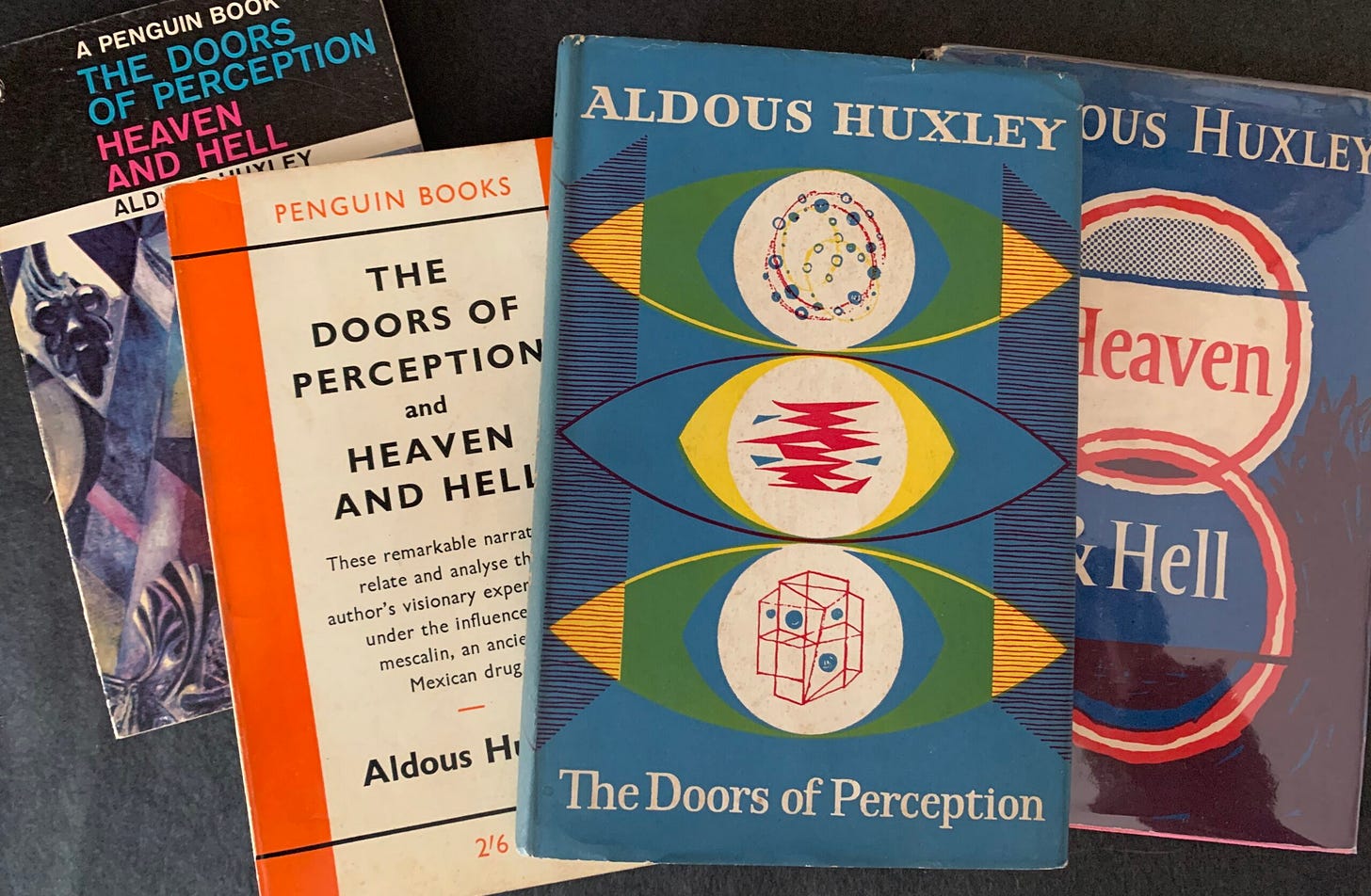

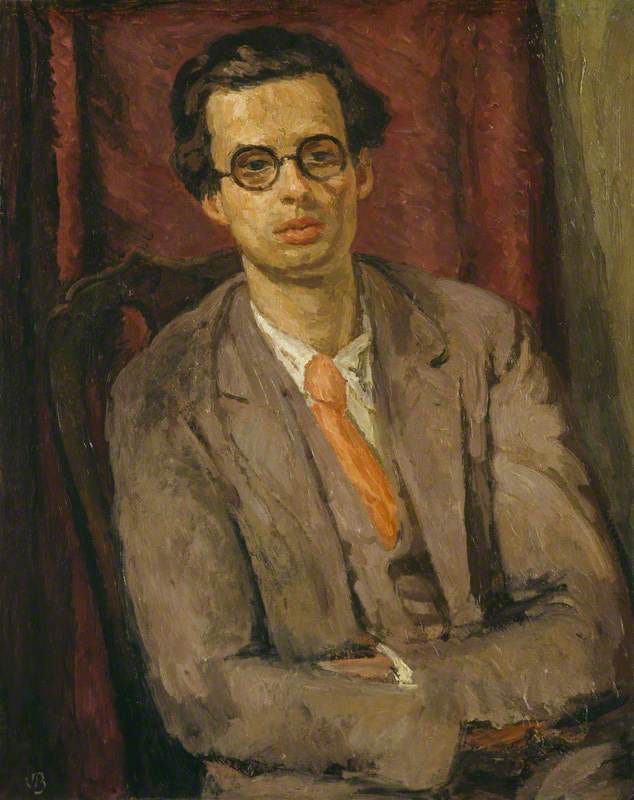

But far from being spontaneous, mystical experiences are rarely unlooked-for. Cultivation, spiritual exercise and self-effort have had many eloquent defenders; even Aldous Huxley was one of them. Huxley, a philosopher and novelist, experimented with mescaline in the 1940s, achieving a brush with transcendence that became the basis for his essays, The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell. Those essays foreground the ability of psychedelics to “open” the doors of the mind and are now classics in psychedelic studies. Like the anonymous participant in the 2015 study published by Psychedelic Medicine (and reviewed eloquently by Michael Pollan for the New Yorker), Huxley suggested that there was no essential difference between a mystical experience triggered by psychedelics and one that was the result of religious ecstasy.

Huxley on mescaline is able to make sense of transcendence as a precise and above all possible experience. Here and now; in theory, anyone can have this, provided they can tolerate the effects of the drug. “The Beatific Vision, Sat Chit Ananda, Being Awareness-Bliss,” Huxley writes, “for the first time I understood, not on the verbal level, not by inchoate hints or at a distance, but precisely and completely what those prodigious syllables referred to.” Huxley’s essays are a playful but fundamentally serious reckoning with the theological idea that mystical experience is a grace, suggesting that “mescaline experience is what Catholic theologians call a ‘gratuitous grace’, not necessary to salvation but potentially helpful and to be accepted thankfully, if made available.”

At the same time, Huxley notes the limitations of presenting mescaline as gratuitous grace. Organized as a series of linked reflections that weave mescaline science together with repeated references to “spiritual exercises,” Huxley always has one eye on what he is not doing: self-effort. I remember reading Doors of Perception as a student curious about psychedelic science, but by the end I was more interested in picking up contemplative practice. Although Huxley conducts his experiments in order to demonstrate the usefulness of mescaline to induce mystical experiences, he is aware of another way: what he calls, following Christian parlance, “the way of Martha.” The spiritual exercises that Huxley mentions obliquely in Doors of Perception are real and seem more pragmatic, too. Many of the obvious disadvantages of relying on psychedelics for one’s mystical experiences Huxley admits and these are clear to anyone familiar with the literature: that psychedelics, while they open the mind, provide short-term highs that do not teach reliable methods for how to maintain contemplative states as long-term traits; that it’s more sustainable to reach the mystic’s “peak” by trudging through the foothills of spiritual exercises than being airlifted thither; that there are dangers associated with replacing cultivation’s “way of Martha” with the gratuitous graces of a “way of Mary.”

Huxley balks at the positivism of mescaline science, whose focus on the expediency of psychedelics tends to bypass the significance of self-effort, but also at theological orthodoxy in the West, where emphasis on passivity in the face of God’s grace winds up precluding the necessity for cultivation. And, he reckons, there is an unhelpful parallel between psychedelics and theology in this regard. “The mescaline taker’s [problem],” muses Huxley, “is essentially the same as that which confronts the quietist…Mescaline can never solve that problem; it can only pose it, apocalyptically, for those to whom it had never before presented itself. The full and final solution can be found only by those who are prepared to implement…the right kind of constant and unstrained alertness.”

Huxley relates how mescaline airlifted him to the peak of contemplative insight, but that, once there, he could see no means of putting contemplation to work – of actually practicing contemplation with “the right kind of constant and unstrained alertness.” So he asks, “How was this cleansed perception to be reconciled with a proper concern with human relations, with the necessary chores and duties, to say nothing of charity and practical compassion?” For Huxley, “Mescaline opens up the way of Mary, but shuts the door on that of Martha. It gives access to contemplation — but to a contemplation that is incompatible with action and even with the will to action, the very thought of action.”

As a scholar-practitioner who spent my formative years training in theology and philosophy, then proceeded to learn contemplation, Huxley’s Doors of Perception speaks to me. I’ve seen the distinction between different types of grace before, but never so viscerally described. Discussions of grace often seem removed from real life. In Huxley’s retelling, grace is not an abstract category but a specific kind of experience. Like Huxley, I appreciate the parallel between grace and psychedelics. But I can’t stomach the notion that grace — be it in the form of a drug or a mystical experience — ends at the gratuitous. Huxley’s most compelling argument actually takes aim at the structural homology between mescaline and the “way of Mary.” This poses some interesting questions to the theologian. Where, I always wonder while reading Doors of Perception, is “habitual grace”? Where is the traditional distinction between grace that arrives out of the blue and grace that grows as a result of cultivation?

Weaving in and out of Huxley’s praise of mescaline’s power to “console our suffering species without doing more harm in the long run than it does good in the short,” is the realisation that the consolations of psychedelics are not sufficient; that there is another path up the mountain of transcendence, one that “includes the way of Martha and raises it, so to speak, to its own higher power.”

If the Doors of Perception has a theological shortcoming, it’s Huxley’s curious neglect of habitual grace. Huxley questions the sufficiency of any gratuitous grace that does not incorporate some degree of cultivation, but in the end includes every mystical experience under the category, “gratuitous grace.” Yet Huxley found that his own experience could not be swapped easily with that of a yogi, even if the peak reached might be the same in both cases. Trudging through those foothills matters. Perhaps it really is a question of habit, of getting to know one’s way around the whole terrain of a mystical experience, slowly, over time; of being able to descend as well as ascend, and help others along the way. The mystic who experiences only the peak can write only about the view from above, and if that ignores the ordeals of the climber, so much the worse for those attempting the hike. It is too much to say that spiritual exercises are gratuitous, even though the grace for which mystics train perception is freely given.

When peak experiences are achieved through psychedelics, spiritual exercises seem ephemeral but aren’t. It’s confusing how often the force of habit is thrown aside in favor of a crypto-theological, “gratuitous grace.” But theology isn’t the problem here. Grace is gratuitous but also habitual; its nature doesn’t need narrowing.

Huxley’s Doors of Perception (along with Heaven and Hell) is a personal favorite whenever I teach mystical theology. It’s full of invitations to think critically about psychedelic science, without taking an a priori negative stance. For me it is very useful to have the theological language of grace re-articulated in terms of chemical intoxicants. It foregrounds so many unexamined assumptions about what it means to say, in mystical theology, that the union with God is freely given. It is an important essay, and should be read by any theologian studying mystical prayer.

References

Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception and Heaven and Hell (Vintage, 2004)

Michael Pollan, “This is Your Priest on Drugs.” New Yorker, 26/05.

Roland R. Griffiths et al, “Effects of Psilocybin on Religions and Spiritual Attitudes and Behaviors in Clergy from Various Major World Religions,” Psychedelic Medicine (2025).

Huxley’s “The Perennial Philosophy” was one of the most formative influences for me as I started on my spiritual journey as a young adult, and I remember everything that he was saying speaking to me on a deep level. What was interesting for me at the time was that this experience of gratuitous grace was granted to me without any effort on my end, and without any consumption of anything (psychedelic or otherwise). I had taken psychedelics many times prior to my spiritual awakening (an atemporal experience of the Uncreated Light when I was 18), but at the time I was completely sober. Prior to the experience, I was also not at all interested in or in any way practicing any sort of spiritual exercises. So I didn’t connect the dots at the time between psychedelics and transcendent experiences, but I did later when I subsequently partook of such substances. For me, the book spoke to my experience directly, and provided me with a framework to understand it. However, it still didn’t explain why this happened to me. To this day I have no rational explanation, only simple faith in God’s grace.

My journey to Christian mysticism has been a long road, and I wandered through many a camp on the way there. I spent some years at Sadhguru’s ashram learning his yogic practices, and he gave a potent analogy for what you’re describing here, although instead of referring to psychedelics, he was talking about a program they hold at Isha called Bhava Spandana, which creates in almost everyone similar transcendental experiences, albeit quite temporary. He called Bhava Spandana a trampoline that you can jump on to peek over a wall to peer into the garden, but only for a moment. The habitual work of contemplation and meditation then is akin to building a ladder that you can then use to climb over the garden wall and actually enter inside.